4 minute read

Many argue that since technology, roads and vehicles have been improved, upgraded, and designed to keep occupants safe, driving has become less of a risk than ever.

In line with this is the belief that even if we choose to be risky on the road, since there are so many systems in place to counteract the dangers of risky driving – we’ll probably be okay.

This train of thought is the product of a few factors:

- Our experiences with driving

- Optimism bias – the natural tendency to think of ourselves as better drivers than others

- Safety measures, policies, and systems

However, do advanced safety policies and systems influence our behaviour for the worst?

According to the literature, there are two types of safety policies…

One form assumes that errors in human behaviour is inevitable and accounts for this by having systems in place that will reduce the severity and consequence of both intentional or unintentional risky behaviour. This can include things like the introduction of airbags, seatbelts or warning systems in cars, or road safety structures like barriers.

The second form tries to force people into adopting safer behaviours by making it harder for them to carry out reckless actions. This is done by altering road conditions to enforce a certain behaviour (i.e. making roads narrow so people must drive slower), or adding preventative measures like speed bumps, enforcement, or fines into the mix.

While both policies are intended to reduce the injury and fatality rate, some studies suggest that these are flawed strategies.

As environmental conditions change people unconsciously adapt their behaviours such that the benefits of taking risks exceed the benefits of avoiding risk. On the roads, some theorists refer to this as risk homeostasis or risk compensation.

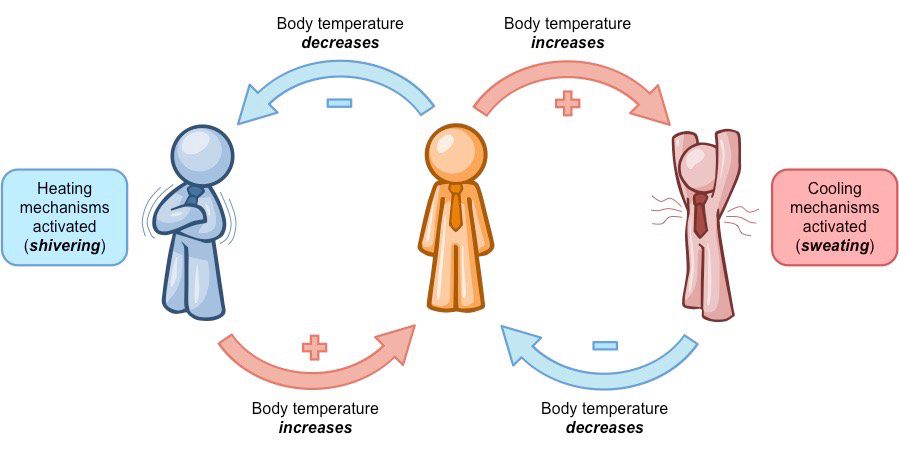

The term homeostasis is commonly used in biology to describe the way the body maintains a stable internal environment despite changing external circumstances, for example, the process your body undergoes to regulate its temperature in various weather conditions.

The image below highlights how the body uses feedback loops to determine when to activate such mechanisms to keep things in a stable (or homeostatic) state.

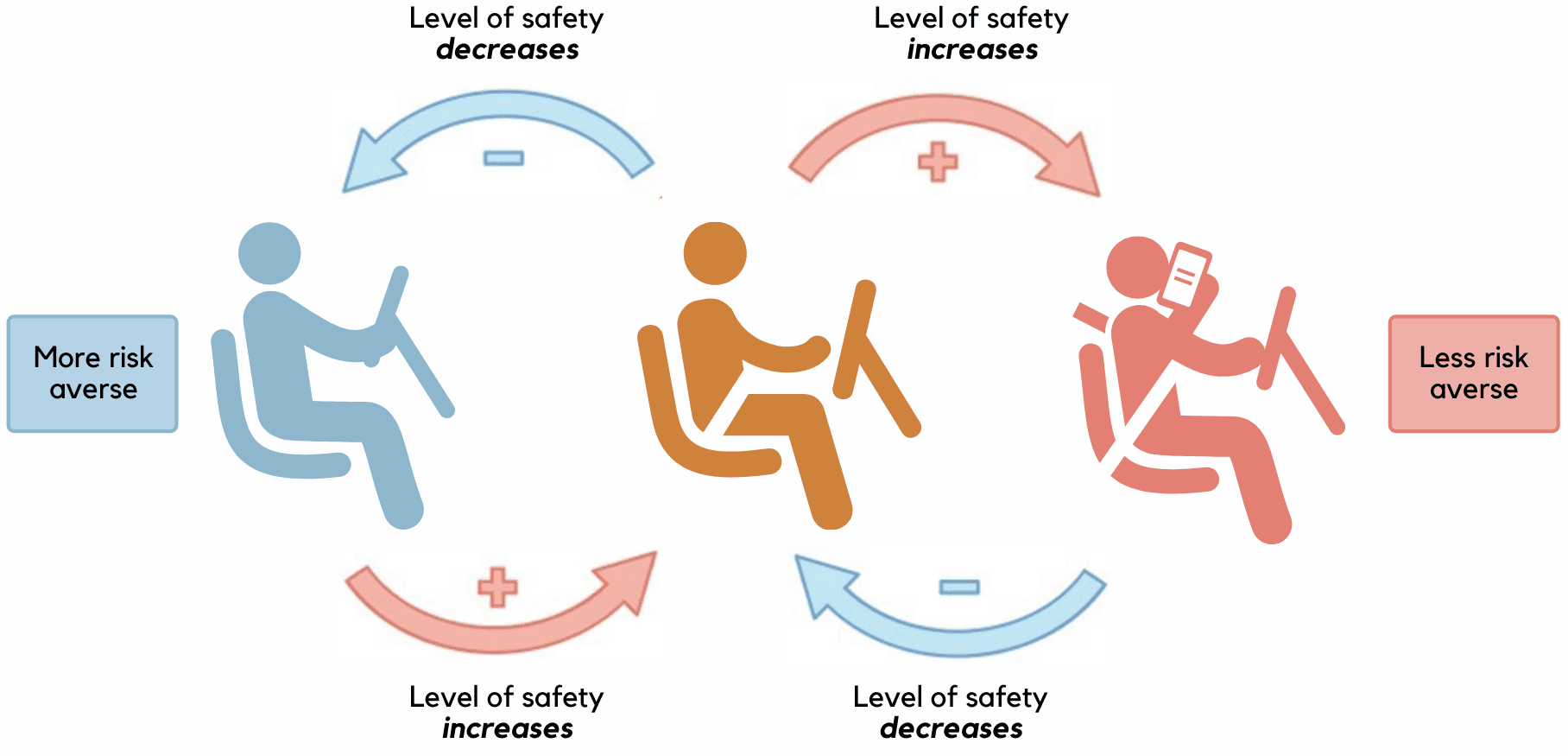

These feedback systems exist all around us and help us to maintain stability in a fluctuating environment. In relation to road safety, risk homeostasis looks something like this:

How do we make decisions about risk and how does risk homeostasis influence them?

As there is never total certainty of any one outcome occurring when a complex decision is made, there is always a level of risk involved in decision making. This means that humans, in many areas of life, must constantly assess the level of risk they are willing to tolerate based on the expected net benefit of carrying out a specific behaviour or action.

According to risk homeostasis, there are four utility factors that influence these decisions:

- The expected benefits of risky behaviour

- The expected costs of risky behaviour

- The expected benefits of safe behaviour

- The expected costs of safe behaviour

On the roads, the cost-benefit analysis between these factors (particularly numbers 1 and 4) are constantly being processed in our heads and playout to look something like this:

“If I speed, I save time (1), but if something goes wrong, I might get fined or crash my car (2). Alternatively, if I travel at the speed limit, my insurance premium could be reduced and I won’t crash my car (3), but then I’ll be losing time and irritating other drivers (4).”

This largely unconscious cost-benefit analysis, in conjunction with optimism bias and perceptions of safety, result in drivers making decisions that sacrifice a degree of safety in favour of other benefits (comfort, peer approval, thrill, time and the like).

One of the first studies to observe this type of behavioural adaption in response to introduced safety measures was carried out in the United States, prior to widespread seatbelt use. Researchers instructed volunteers to drive a 5-horsepower go-cart but gave them the option to do so either using or not using a seatbelt. Completing the course multiple times, it was found that when participants chose to use seatbelts, they moved along the track at higher speeds.

A similar experimental study was carried out in the Netherlands, except this time, habitual non-seatbelt users were asked to buckle up when driving real cars on everyday roads. When strapped in with a seatbelt, users were observed driving and merging at higher speeds, tailgating and braking later.

Similar studies done on systems such as the Anti-lock Brake System (ABS) yielded corresponding results. One study looking into taxi drivers found that those with ABS systems installed exhibited more cases of extreme deceleration (hard braking) than those who didn’t.

If technological innovation breeds a sense of security and therefore makes us more willing to take risks, how do we train drivers not to throw away the safety advantages afforded by better-designed cars and roads?

–

To find out more about our programs click HERE.

Take the Pledge to Road Safety HERE or subscribe to our monthly Newsletter ‘Road Matters’ HERE.

Get involved in the conversation and follow us on: